by Tanya Amyote

Allyship 101

“The Guide to Allyship”, created by Amélie Lamont, is a starter guide to becoming a more thoughtful and effective ally. In it, they share:

“Anyone has the potential to be an ally. Allies recognize that though they’re not a member of the underinvested and oppressed communities they support, they make a concerted effort to better understand the struggle, every single day.

Because an ally might have more privilege and recognizes said privilege, they are powerful voices alongside oppressed ones.”

Now, before you object to being accused of having privilege, let’s clarify exactly what that means.

Privilege, in this context, does not mean financial wealth. Privilege, in this context, does not mean that your life has been without conflict, difficulty, or trauma. Privilege, in this context, means that the conflicts, difficulties, and/or traumas in your life have not been caused or exacerbated by your race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or ability differences.

As a white, cisgender female, my inherent privilege is undeniable; as an ally, it is my responsibility to leverage that privilege, and serve as a voice of support, ensuring that members of underrepresented communities are heard, included, validated, and engaged.

The Edge team recently committed to an inspiring and enlightening Diversity & Inclusion training program and partnership with Poh Lin Khoo of Khoo Consulting, a woman-owned, small business based in Minnesota. Poh Lin and her team, through their tailored curriculum, help companies to grow crucial expertise in creating an inclusive work culture, enabling all employees to bring their authentic selves to the workplace. This insight and education can then be carried forward to clients, through the development of relevant marketing messages, reflecting and resonating with diverse and global audiences.

Our team was deeply moved by Poh Lin’s personal history as a survivor of the racial riots in Malaysia on May 13th, 1969, and her drive to “shape (her) own destiny”.

From our first session with Poh Lin, two other key takeaways have continued to stick with me:

- The danger of a single story; and

- Equality versus equity versus justice.

The Danger of a Single Story

In her renowned TED Talk, Nigerian-born author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speaks about her experience of moving to the United States to go to university. Adichie came from a middle-class family; her father was a professor, her mother was an administrator, they had live-in domestic help, and English is the official language of Nigeria.

Upon Adichie’s arrival at university, her American roommate was shocked that she spoke English so well; that she knew how to use a stove; that she listened to Mariah Carey as opposed to “tribal music”.

Before they had even met, the roommate’s biases, conscious or not, had led her to make assumptions about Adichie, based on a single, incomplete story: Her country of origin. Well-meaning though the roommate surely was, this myopic framing of Adichie as the poor, African girl, precluded any possibility of the roommates connecting as equals.

By mistakenly imagining Adichie through one singular lens, as opposed to seeing her as a woman with a multi-faceted identity formed by a lifetime of experiences, the roommate sees an incomplete portrait in which the single story is the only story.

Although they came from vastly different corners of the world, a simple change in perspective could have veered the roommate toward the realization of their intersecting identities: They were both women, students new to adulthood, both Mariah Carey fans, both daughters of teachers, and on and on.

In the words of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.”

Equality versus equity versus justice

In this November 2020 piece by George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health, equity and justice are outlined as, “Equity is a solution for addressing imbalanced social systems. Justice can take equity one step further by fixing the systems in a way that leads to long-term, sustainable, equitable access for generations to come.”

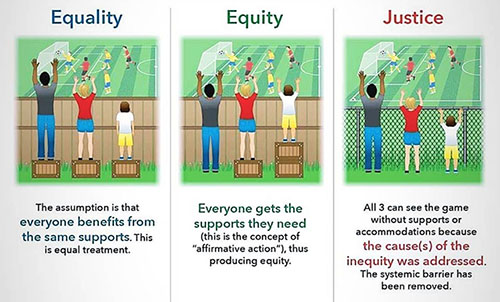

In the Equality image on the left, the available resources (the crates) are allocated equally amongst the three people watching the soccer game. Equality does not account for varying levels of need; the same resources are divided evenly, regardless of any other factors.

In the Equity image, the resources are allocated such that each person receives the support they need in order to level the proverbial playing field.

Lastly, in the case of justice, the root cause of the inequity is addressed: The inherent issue (the systemic barrier) is the fence. By changing the fence, no supports or accommodations are required to enable all three people of varying positions to be included.

To revisit Lamont’s “The Guide to Allyship”, the author shares important Dos and Don’ts of true allyship. This piece is invaluable to those of us who are learning to have an awareness of our implicit biases, and are using privilege to amplify suppressed voices.

As allies, it is our responsibility to take it upon ourselves to use the tools around us to listen, learn, lift, and support.

About the Author

Tanya Amyote joined the Edge team in 2016, as marketing assistant, Excel guru, and token Canadian.

When not solving the world’s pivot table problems, Tanya is an avid reader, fountain pen user, and outspoken advocate for awareness of Osteogenesis Imperfecta (brittle bone disease). On May 6th, Wishbone Day, we’ll be wearing yellow to raise awareness of the varied, full, and meaningful lives of people with O.I., including Tanya and her 9-year-old son, James.